by Ethan Begle, Technical Service

For many farmers, this was the year in which waiting through April for warm, dry weather didn’t equal better conditions in May. It’s another reminder to spread out your planting risk. If you had to plant in less-than-ideal conditions, it was better to plant ahead of a rain to keep the soil wet enough for the roots to proliferate (this is assuming you were aggressive with your closing wheels to break up the sidewall). When it’s wet, closing the furrow becomes more difficult. Since wet soil does not crumble very easily the sidewall can be pulled up in chunks. In drier soil the sidewall would crumble nicely; however, if you believe you must get things planted with more days of rain on the way, these chunks will dry out and crumble more after the rain. This is when some farms (using a drag chain) can have success smoothing out those lumps. Using Keetons to firm the seeds into moisture means less risk of the furrow drying out too fast before emergence. In addition to this, locking the seeds firmly into the bottom allows for more aggressive closing action.

You can see in the photos that at my farm, planting conditions (southern Indiana) were much wetter than I prefer. There were good soil conditions in early April (and I did plant a field), but I still like the May temperatures for more even emergence. Additionally, it gives my cover-cropped fields time to grow more. Nine years out of ten, I’m faced with what most would consider wet planting conditions (can easily form a ball of soil with my hand). Although, I typically don’t see this as a negative. I pushed ahead to plant because another week of rain was forecasted and I would have had to change plans, going with an earlier maturity seed.

As I touched on in April’s newsletter, tilling a field when it’s wet in order to “dry” it out causes more compaction than just planting the field while only disturbing the soil with the closing wheels. The residue left on the field provides a cushion for tires to follow. Plus, minimal disturbance keeps the mud below ground where it can’t plug up the planter. This is a good time to keep the row cleaners up so as not to expose bare soil. No-tillers will be planting into wetter soils more often than dry. One of the benefits to no-tilling is the moisture savings later in the season when it’s scorching hot. Use residue and living roots to provide that barrier to the mud. However, fields that are chronically wet (ponding water) need to be managed differently. Lighter planting rigs make wet planting easier, which can be done by only having enough seed and fertilizer for the field or filling up more often helps.

The field needs to be dry enough to carry the equipment across without making much of a tire track.

Keep in mind part of the reason no-tillers are seen to be waiting in early spring is for warmer temperatures. If I had planted in April, temperatures would be cooler, and I would fully recommend putting on starter fertilizer to promote crop nutrient uptake. Having plant food near the seed after emergence gives the energy boost it needs to survive the cool temps. Biologicals are the perfect recipe for in-furrow options to aid emergence in cool wet conditions. Live biology generates heat in their natural process to digest residue and survive.

No-tillers should always be faced with moisture at planting. It takes water for the seed to germinate and make nutrients available for the plant to grow. When dealing with saturated fields, less disturbance is more beneficial. The greatest risk to wet planting is that the faucet turns off and dry weather cements the compaction in place for the growing season. Patience is required but, in real life, other factors can come into play as to when it’s no longer acceptable to wait.

At the time of this writing, I did get adequate emergence on these wetter acres (>92%). The fields received a couple inches of rain since planting. The nature of farming means this could go either way, with many farms receiving heavier rains that create anerobic conditions in the field. The erosion from these storms is what I’m trying to prevent.

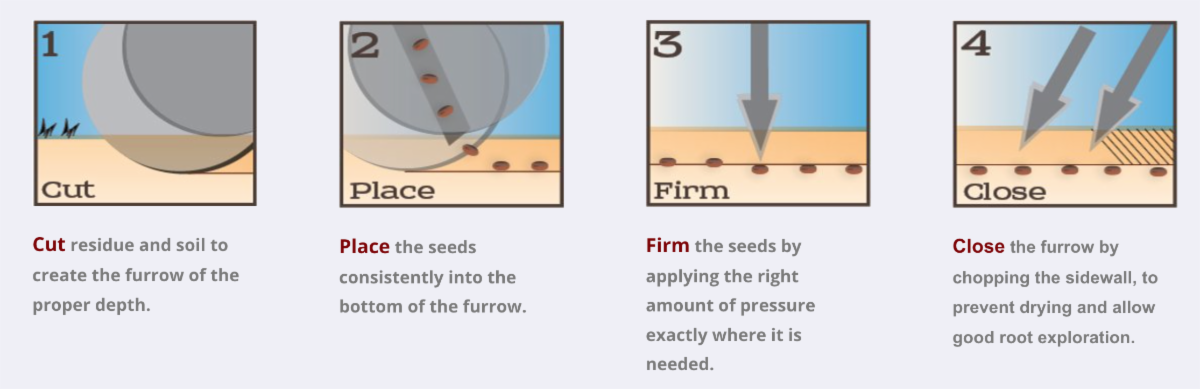

This writing is to share thoughts on not-so-ideal conditions. When the weather cooperates with dry conditions you should not need rain for at least 48 hours after planting. Firming the seed into moisture is the biggest factor in making this successful. Consider if your planter is set up to handle the four steps of planting. Cut a clean furrow, place the seed into the bottom, firm the seed, and close the furrow completely without packing the soil tight to encourage Oxygen exchange. I’d be glad to talk more on these topics, feel free to call 785-332-9117.